The Fourth “F” — Fawning

Most people are familiar with the classic trauma responses: fight, flight, and freeze. But trauma research has increasingly recognized a fourth response that often hides in plain sight: fawning.

Most people are familiar with the classic trauma responses: fight, flight, and freeze. But trauma research has increasingly recognized a fourth response that often hides in plain sight: fawning.

In her book Fawning: Why the Need to Please Makes Us Lose Ourselves — and How to Find Our Way Back, psychologist Dr. Ingrid Clayton describes fawning as a hybrid trauma adaptation—a subconscious survival strategy in which a person moves toward the source of threat rather than away from it. Instead of protecting ourselves through avoidance or defense, we attempt to secure safety by appeasing, pleasing, or over‑accommodating the person who feels unsafe or unpredictable.

What Fawning Is (and Isn’t)

Fawning is often mistaken for people‑pleasing or codependency, but the underlying motivation is different.

People‑pleasing is typically about wanting to be liked.

Codependency involves enmeshment and lack of boundaries.

Fawning, however, is a trauma‑based response rooted in fear, insecurity, and the need for emotional or physical safety.

Fawning shows up when we feel inexplicably drawn closer to someone who causes harm or instability—something that doesn’t make logical sense but makes emotional survival sense. Instead of withdrawing from pain or dysfunction, we move toward it, hoping to minimize conflict or avoid abandonment.

Why Fawning Keeps Us Stuck

Fawning helps explain why people:

Stay in harmful relationships

Remain in toxic workplaces

Tolerate dysfunctional environments

Ignore red flags that seem obvious to others

Like all trauma responses, fawning originally served a purpose—it helped someone survive an unsafe environment. But when it becomes an automatic, lifelong pattern, it can lead to resentment, burnout, loss of identity, and chronic self‑silencing.

Signs You Might Be “Fawning”

If you’ve ever found yourself doing the following, you may be operating from a fawn response:

Apologizing to someone who hurt you in an attempt to defuse tension

Ignoring a partner’s harmful behavior because speaking up feels dangerous

Staying up late or overworking to stay on your boss’s “good side”

Befriending bullies or difficult people to reduce conflict

Worrying constantly about saying the “wrong” thing

Shifting your personality, preferences, or opinions for approval

At its core, fawning is about earning safety through compliance—a strategy that may once have been protective but becomes harmful when it replaces healthy boundaries.

How Therapy Helps Break the Fawn Response

Healing requires learning new ways to experience safety, connection, and self‑expression. Several evidence‑based therapies can support this process:

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Helps identify survival‑based beliefs (“I’m only safe if everyone is happy with me”) and replace them with healthier cognitions.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT): Strengthens emotional regulation, boundary‑setting, and distress tolerance.

Internal Family Systems (IFS): Helps explore protective parts of the self that developed the fawn response.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR): Reprocesses traumatic memories that created the pattern.

Somatic Experiencing: Helps the nervous system learn safety through body‑based awareness and regulation.

Fawning is not a character flaw—it’s a trauma imprint. With the right support, people can reconnect with their authentic selves, develop healthy relationships, and rebuild a sense of internal safety.

References

Clayton, I. (2023). Fawning: Why the need to please makes us lose ourselves—and how to find our way back.

Herman, J. L. (2015). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence—from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

Linehan, M. M. (2015). DBT skills training manual (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton.

Schwartz, R. C. (2021). No bad parts: Healing trauma and restoring wholeness with the internal family systems model. Sounds True.

Shapiro, F. (2018). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy (3rd ed.): Basic principles, protocols, and procedures. Guilford Press.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

The Grieving Body: How Loss Lives in the Body

Grief is one of the most painful and disorienting human experiences. Many describe it as feeling as though a part of themselves has been cut away—an absence so profound it is felt not only emotionally, but physically. In The Grieving Brain, psychologist and neuroscientist Mary‑Frances O’Connor, PhD, offers compelling scientific and clinical insight into why grief feels the way it does and how loss fundamentally reshapes the body and brain.

A Book Review of The Grieving Body By Mary‑Frances O’Connor, PhD.

Grief is one of the most painful and disorienting human experiences. Many describe it as feeling as though a part of themselves has been cut away—an absence so profound it is felt not only emotionally, but physically. In The Grieving Brain, psychologist and neuroscientist Mary‑Frances O’Connor, PhD, offers compelling scientific and clinical insight into why grief feels the way it does and how loss fundamentally reshapes the body and brain.

O’Connor’s work challenges the common misconception that grief is “all in our head.” Instead, she demonstrates that grief is a whole‑body experience, rooted in biology, attachment, and survival.

Grief as a Biological Experience

According to O’Connor, bereavement activates powerful physiological responses. The death of a loved one can trigger increased heart rate, elevated blood pressure, heightened stress hormones, and inflammatory processes throughout the body. These responses occur because close relationships are not simply emotional bonds—they are part of our survival system.

Humans are wired for attachment. When we form a close bond, our nervous systems become attuned to another person’s presence, habits, and rhythms. Over time, the brain comes to rely on that relationship in ways that operate largely outside of conscious awareness. The sudden loss of that bond places the body into a state of alarm, as though something essential to survival has disappeared.

This helps explain why grief can feel so physically distressing: the body is reacting to danger, not metaphor.

The Loneliness of Loss and the Brain’s Search

One of O’Connor’s central themes is the brain’s effort to make sense of absence. After a loss, the world can feel painfully unfamiliar. Widows and widowers often describe a deep loneliness that cannot be easily named—not merely the absence of companionship, but the absence of a shared reality.

O’Connor explains that grief is not just cognitive (“I know they are gone”), but also emotional and neurological. The brain continuously predicts where our loved one will be, how they will respond, and how we will move through the world together. After a death, the brain must repeatedly confront the mismatch between expectation and reality.

This ongoing process of recalibration is exhausting and can leave grieving individuals feeling confused, unfocused, or emotionally overwhelmed.

The Body Keeps the Score of Loss

A particularly sobering contribution of The Grieving Brain is O’Connor’s discussion of the physical risks associated with bereavement. Research shows that chronic health conditions may emerge or worsen sooner following the death of a loved one. The prolonged stress of grief can accelerate inflammation, weaken immune functioning, and exacerbate underlying medical vulnerabilities.

O’Connor highlights the well‑documented “widowhood effect,” which shows a significantly increased risk of illness and mortality following spousal loss. In the first one to three months after a wife’s death, a surviving husband’s risk of death approximately doubles. Following a husband’s death, a surviving wife’s risk increases by approximately 50 percent. While this elevated risk decreases over time, bereavement is clearly a period of heightened physical vulnerability.

In rare but real cases, sudden cardiac events—sometimes referred to as “broken heart syndrome”—can occur following acute emotional loss.

Clinical Implications and Compassionate Care

O’Connor’s work carries an important message for both clinicians and bereaved individuals: grief deserves medical and psychological attention. Survivors are often encouraged to “be strong” or “move on,” yet the science suggests the opposite—grief requires care, monitoring, and compassion.

Medical follow‑ups, mental health support, and reduced self‑criticism during early bereavement are not indulgent; they are protective. Understanding grief as a biological process may also relieve some of the shame grieving individuals feel when their bodies seem to “betray” them.

A Grounded, Hopeful Perspective

While The Grieving Brain is rooted in neuroscience, it is ultimately a deeply humane work. O’Connor does not offer quick solutions or timelines. Instead, she emphasizes that adaptation after loss takes time and that the brain is capable of relearning a world forever changed.

This book is particularly valuable for grief therapists, medical professionals, and anyone navigating loss. It validates the experience of grief as both profoundly painful and deeply human—something that happens not because we are weak, but because we are bonded.

Final Reflections

The Grieving Brain reframes grief as a biological, relational, and survival‑based experience. Mary‑Frances O’Connor reminds us that love does not end when someone dies—and neither does the body’s memory of that love.

Grief lives in the body because love lived there first.

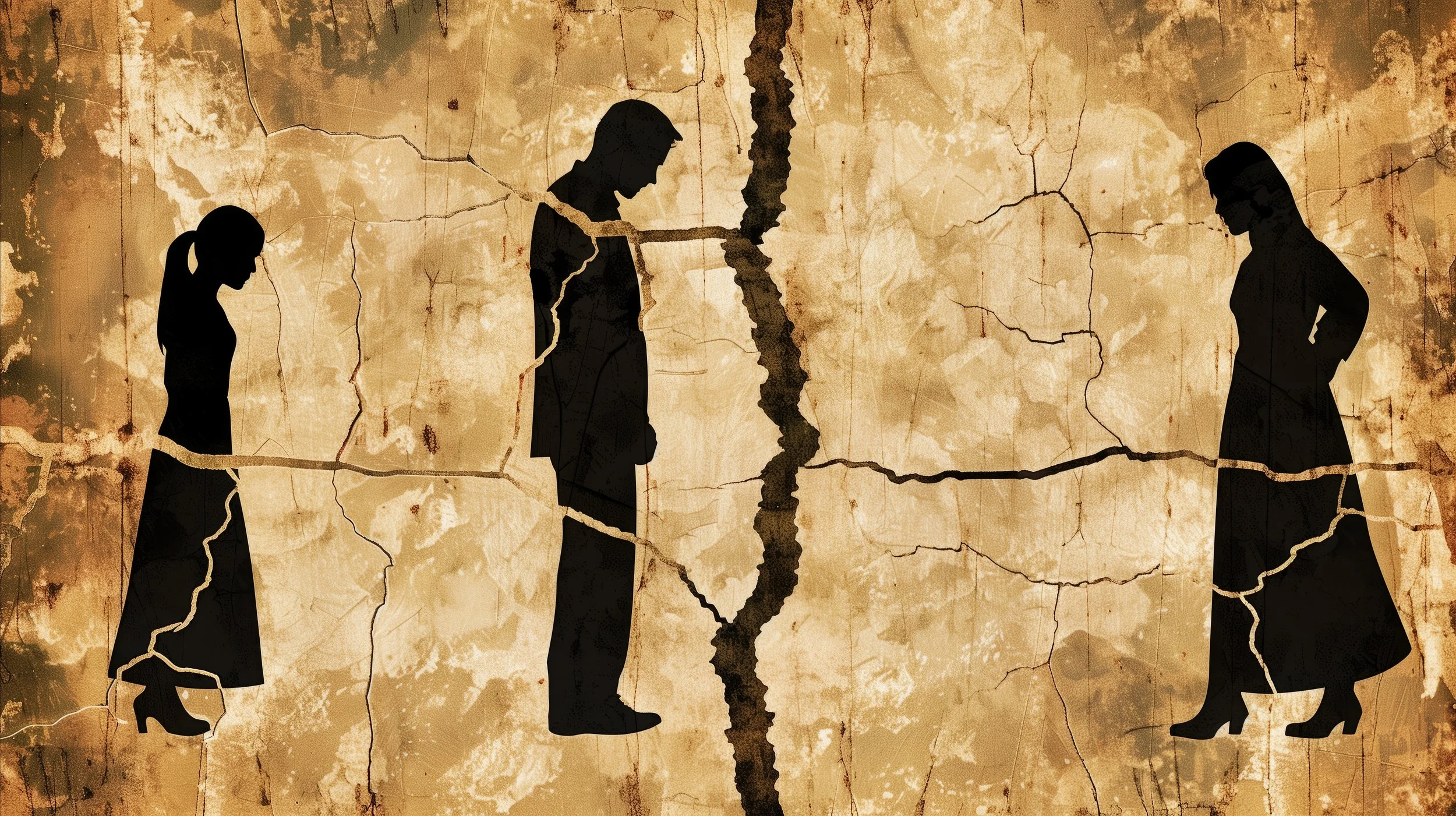

Estrangement and Fractured Families

Family estrangement is one of the most emotionally painful and least openly discussed experiences individuals face across the lifespan. Estrangement is commonly defined as the cessation or significant reduction of regular contact between two or more family members (Agllias, 2017). While often assumed to be permanent, estrangement can be fluid—relationships may move in and out of periods of distance, reconciliation, and renewed rupture over time.

Family estrangement is one of the most emotionally painful and least openly discussed experiences individuals face across the lifespan. Estrangement is commonly defined as the cessation or significant reduction of regular contact between two or more family members (Agllias, 2017). While often assumed to be permanent, estrangement can be fluid—relationships may move in and out of periods of distance, reconciliation, and renewed rupture over time.

Despite its prevalence, estrangement remains highly stigmatized. Many individuals hesitate to speak about fractured family relationships due to the pervasive cultural belief that others have “perfect families.” This silence can deepen feelings of shame, isolation, and self‑doubt, particularly when the estrangement was not mutually chosen.

One‑Sided Estrangement and Adult Child–Parent Relationships

Estrangements can be especially difficult when they feel one‑sided, such as when an adult child decides that the relationship with a parent is too emotionally harmful or complex to maintain. Adult children may choose distance to protect themselves from ongoing conflict, criticism, boundary violations, or unresolved trauma. Parents, in turn, may experience confusion, grief, anger, or disbelief, interpreting the cutoff as rejection or betrayal rather than self‑preservation.

Research suggests that many adult‑initiated estrangements stem from longstanding relational patterns rather than isolated events, including unmet emotional needs, poor communication, or perceived lack of acceptance (Carr et al., 2015).

Intergenerational Patterns of Estrangement

For some families, estrangement is not an isolated occurrence but part of a repeating intergenerational cycle—grandfather to father, father to son. These patterns often reflect unresolved family trauma, rigid relational roles, or inherited beliefs about power, loyalty, and closeness. Without intervention or conscious effort, these fractured dynamics can be unintentionally passed down, normalizing emotional cutoff as a means of conflict resolution.

Values Conflicts and Fear of Rejection

Fear of estrangement may also arise before a rupture occurs, particularly when an adult child makes lifestyle choices that differ sharply from parental values. Differences related to identity, relationships, religion, cultural norms, or personal beliefs can strain family bonds. Individuals may feel torn between authenticity and belonging, asking themselves:

Is it better to stand firm when I cannot change my beliefs, or can I continue to love someone while not approving of their decisions?

These tensions highlight the complexity of family relationships and the emotional labor required to balance personal integrity with relational connection.

Emotional Impact of Estrangement

Family estrangement can evoke emotions similar to ambiguous loss—grief without closure. Individuals may experience sadness, guilt, anger, relief, or a confusing mix of all four. Holidays, life milestones, and social comparisons often intensify this pain, reinforcing the sense of being “different” or excluded from a societal ideal of family unity (Boss, 2006).

Moving Forward: Care, Compassion, and Support

Regardless of the specific circumstances, it is essential to recognize that family estrangement is more common than commonly acknowledged—and that those experiencing it are not alone. Prioritizing self‑care, establishing supportive relationships outside the family system, and seeking professional counseling can help individuals process grief, clarify boundaries, and navigate decisions around contact or reconciliation.

Healing does not require minimizing pain or forcing forgiveness. Instead, it involves honoring one’s emotional experience, cultivating self‑compassion, and making choices that support long‑term well‑being.

References

Agllias, K. (2017). Missing families: The adult child’s experience of parental estrangement. Journal of Social Work Practice, 31(4), 459–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2017.1326476

Boss, P. (2006). Loss, trauma, and resilience: Therapeutic work with ambiguous loss. W. W. Norton & Company.

Carr, K., Holman, A., Abetz, J., & Kellas, J. (2015). Giving voice to the silence of family estrangement. Journal of Family Communication, 15(2), 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2015.1013106

Hill, J. (2023). Family estrangement: Establishing boundaries and navigating loss. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com

Understanding the Quarter-Life Crisis

The term quarter-life crisis describes a period of emotional upheaval and identity questioning that commonly occurs during early adulthood, roughly between the mid‑20s and mid‑30s. According to psychologist Claire Hapke, PsyD, LMFT, this phase is marked by uncertainty, pressure, and reassessment as young adults confront major life decisions with fewer clearly defined milestones than previous generations (Hapke, 2013).

The term quarter-life crisis describes a period of emotional upheaval and identity questioning that commonly occurs during early adulthood, roughly between the mid‑20s and mid‑30s. According to psychologist Claire Hapke, PsyD, LMFT, this phase is marked by uncertainty, pressure, and reassessment as young adults confront major life decisions with fewer clearly defined milestones than previous generations (Hapke, 2013).

Changing Pathways to Adulthood

Historically, adulthood followed a relatively predictable sequence:

Graduation

Full-time employment

Marriage

Home ownership

Parenthood

Retirement

In contrast, today’s young adults often pursue extended education to increase earning potential, begin adulthood with significant student loan debt, and delay traditional milestones such as marriage and home ownership. Current trends show that the average age of marriage has shifted later—approximately age 29 for men and 27 for women in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023). These changes have disrupted previously accepted timelines for “success” and stability.

Developmental Tasks of the Quarter-Life Period

During this stage, individuals typically work through several key developmental tasks:

Transitioning from school to the workforce

Moving out of the family home

Working toward financial independence

Making autonomous decisions

Renegotiating the caregiver–child relationship with parents

As the structured environment of education ends, young adults encounter the challenge of self‑direction. With fewer external guidelines, many struggle with questions such as Who am I? and What am I supposed to be doing with my life? Research suggests individuals may experience up to seven career changes between the ages of 18 and 30, contributing to feelings of instability and disorientation (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022).

Emotional and Behavioral Effects

The uncertainty associated with a quarter-life crisis can manifest in a variety of emotional and behavioral responses, including:

Depression

Anxiety

Decreased motivation

Low self‑esteem and self‑worth

Social isolation

Insecurity

Substance misuse

Increased engagement in risky behaviors

Many individuals describe this phase as feeling “cast out to sea”—expected to navigate adulthood independently without a clear map or destination.

Common Quarter-Life Crisis Experiences

Two patterns commonly emerge during this period:

“Locked In”

Individuals may secure stable employment with competitive pay yet feel deeply dissatisfied or trapped. Although externally successful, they experience internal conflict and diminished fulfillment.

“Locked Out”

Others encounter repeated rejection and frustration when attempting to enter desired career fields, often due to limited experience or competitive job markets. This can foster feelings of inadequacy and hopelessness.

Generational Pressures and Social Comparison

Sally White notes that millennials (born approximately between 1980 and 2000) are frequently labeled as narcissistic or entitled, yet these characterizations fail to account for the structural and economic challenges shaping their experiences (White, 2016). The traditional model of success no longer aligns with current realities, and constant social comparison—amplified through social media—can intensify feelings of failure and self‑doubt.

White emphasizes that comparing one’s behind‑the‑scenes struggles to others’ curated online successes is both unrealistic and harmful, often exacerbating quarter-life distress.

Support and Growth During a Quarter-Life Crisis

Experiencing a quarter-life crisis does not indicate personal failure. Instead, it reflects a normative developmental transition within a rapidly changing social and economic landscape. Working with a professional counselor can be beneficial in addressing this phase by focusing on:

Increasing self‑esteem and self‑worth

Engaging in identity and self‑exploration

Differentiating external expectations from internal values

Clarifying personal wants and needs

Exploring, committing to, or recommitting to core values

With appropriate support, individuals can use this period as an opportunity for growth, self‑definition, and intentional life planning.

References

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). Number of jobs, labor market experience, and earnings growth among Americans. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.bls.gov

Hapke, C. (2013). Understanding the quarter-life crisis. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com

U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). Median age at first marriage: 1890 to present. https://www.census.gov

White, S. (2016). Quarter-life crisis: Defining millennial success [TED Talk]. https://www.ted.com/talks/sally_white_quarter_life_crisis_defining_millenial_success

Understanding Ambiguous Loss in 2025: Navigating Grief Amid Global Uncertainty

Ambiguous loss is a profound form of grief that occurs without clear closure or resolution. Coined by Dr. Pauline Boss in the 1970s, this concept describes situations where a person experiences loss without the traditional markers of death or finality. Such losses can be particularly challenging because they often go unrecognized by others, leading to feelings of isolation and confusion.

Ambiguous loss is a profound form of grief that occurs without clear closure or resolution. Coined by Dr. Pauline Boss in the 1970s, this concept describes situations where a person experiences loss without the traditional markers of death or finality. Such losses can be particularly challenging because they often go unrecognized by others, leading to feelings of isolation and confusion.

Types of Ambiguous Loss

Dr. Boss identifies two primary types of ambiguous loss:

Physical Absence with Psychological Presence: This occurs when a person is physically absent but still psychologically present. Examples include a loved one who has gone missing, a spouse who has left without explanation, or a parent who has abandoned the family.

Psychological Absence with Physical Presence: In this case, a person is physically present but psychologically absent. This can manifest in conditions like Alzheimer's disease, brain injuries, or severe mental illnesses, where the individual's cognitive functions are impaired, leading to a loss of the person as they once were.

Recent Insights and Research

Recent studies have expanded our understanding of ambiguous loss, highlighting its impact on various populations and contexts:

Caregivers of Individuals with Dementia: Research indicates that caregivers of individuals with dementia often experience ambiguous loss due to the gradual cognitive decline of their loved ones. This type of loss can lead to prolonged grief and challenges in caregiving.

Impact of Social Movements: Social movements and societal changes can also lead to ambiguous loss. For instance, communities affected by systemic racism may experience a loss of safety and identity, which is difficult to address due to its abstract nature.

Global Crises: Events like natural disasters, political unrest, and pandemics can create situations of ambiguous loss, where individuals lose their sense of normalcy and security without a clear endpoint.

Coping Strategies

Coping with ambiguous loss requires unique approaches, as traditional grieving processes may not apply. Here are some strategies:

Acknowledge the Loss: Recognizing and naming the ambiguous loss can validate the feelings of grief and help individuals begin the healing process.

Seek Support: Connecting with others who understand the experience, such as support groups or therapists, can provide comfort and reduce feelings of isolation.

Practice Self-Care: Engaging in activities that promote well-being, such as exercise, mindfulness, and hobbies, can help individuals manage stress and maintain resilience.

Create Meaning: Finding new ways to create meaning in life, such as through art, community involvement, or personal growth, can help individuals navigate the uncertainty of ambiguous loss.

When to Seek Professional Help

If you find that the feelings associated with ambiguous loss are overwhelming or persistent, it may be beneficial to seek professional help. Therapists trained in grief and loss can provide support and strategies tailored to your specific situation.

At Summit Family Therapy, we understand the complexities of ambiguous loss and are here to support you through your journey. If you're struggling with unresolved grief, consider reaching out to our team for guidance and assistance.

Sources

Boss, P. (1999). Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief. Harvard University Press.

Kucukkaragoz, H., & Meylani, R. (2024). Ambiguous losses and their traumatic effects: A qualitative synthesis of the research literature. Batı Anadolu Eğitim Bilimleri Dergisi, 15(2), 721-755.

Ahmed, A., & Forrester, A. (2025). Mental health challenges of enforced disappearances: A call for research and action. International Journal of Social Psychiatry.

Danon, A., Dekel, R., & Horesh, D. (2025). Between mourning and hope: A mixed-methods study of ambiguous loss and posttraumatic stress symptoms among partners of Israel Defense Force veterans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 17(4), 795-804.

Testoni, I., et al. (2023). Ambiguous loss and disenfranchised grief in formal care settings: A study among dementia caregivers. Journal of Aging Studies, 61, 100986.

Kor, K. (2024). Responding to children's ambiguous loss in out-of-home care: A qualitative study. Child & Family Social Work, 29(1), 72-80.

Mac Conaill, S. (2025). Long-term experiences of intrapersonal loss, grief, and change in people with acquired brain injury: A phenomenological study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 47(5), 1012-1020.

Zasiekina, L., Abraham, A., & Zasiekin, S. (2023). Unambiguous definition of ambiguous loss: Exploring conceptual boundaries of physical and psychological types through content analysis. East European Journal of Psycholinguistics, 10(2), 182-200.

Breen, L. (2025). 'Few people thought grief was a worthy topic': Reflections on two decades of research in hospice and palliative care. The Australian Research Magazine.

Life Transitions: 8 Tips for Navigating Change with Grace and Resilience

Ambiguous loss is a profound form of grief that occurs without clear closure or resolution. Coined by Dr. Pauline Boss in the 1970s, this concept describes situations where a person experiences loss without the traditional markers of death or finality. Such losses can be particularly challenging because they often go unrecognized by others, leading to feelings of isolation and confusion.

What Is a Life Transition?

Life transitions are moments of change that invite us to pause and reflect on who we are and who we want to become. While transitions can happen at any stage of life, they often feel particularly intense during midlife, retirement, or other pivotal periods. It’s normal to feel uncertain, anxious, or even sad during these times—these emotions are part of what it means to be human.

Examples of Life Transitions:

Getting married

Pregnancy or becoming a parent

Divorce or separation

Leaving home or moving to a new place

Empty nest syndrome

Career change or job loss

Health challenges or serious illness

Significant loss (person, pet, or anything important)

Retirement

Why Do Transitions Feel Overwhelming?

Change can feel like stepping into the unknown. Our minds naturally crave predictability, so when the familiar shifts, we may feel anxious, vulnerable, or even mourn the life we once had. Sometimes this stress can show up as trouble sleeping, changes in appetite, or even feelings of depression or anxiety. When it becomes too much to handle on your own, it may even meet the criteria for an adjustment disorder, which is a normal response to major life changes (O'Donnell et al., 2019).

Finding the Silver Lining

Though change can be challenging, it also carries opportunities for growth. Research shows that successfully navigating transitions can strengthen resilience, boost confidence, and increase emotional awareness (Peng et al., 2025). You may discover new skills, uncover what truly matters to you, or develop a deeper sense of self. Even transitions we didn’t choose can bring unexpected benefits.

Coping with Change: Evidence-Based Strategies

Here are ways to care for yourself and navigate life’s transitions with compassion and clarity:

Acknowledge Your Emotions: Allow yourself to feel whatever arises—fear, sadness, excitement, or relief. Naming your emotions validates them and begins the healing process.

Reach Out for Support: Lean on friends, family, or support groups. Sharing your experience reminds you that you are not alone.

Practice Self-Compassion: Be gentle with yourself. Adjusting to change takes time, and it’s okay to stumble along the way.

Take Care of Your Body: Sleep, nutrition, and movement all influence your emotional well-being. A healthy body supports a resilient mind.

Use Active Coping Strategies: Problem-solving, goal-setting, or positive reframing can help you feel more in control of your new circumstances (Sundqvist et al., 2024).

Reflect on Your Values: Clarifying what matters most to you can guide your decisions and help you move forward with intention.

Build New Routines: Small, consistent habits create stability amidst uncertainty.

Allow Yourself Time: Life transitions are a journey. Celebrate small wins and notice how you grow along the way.

When to Seek Professional Help

If the stress of change feels unmanageable, or if you notice persistent sadness, anxiety, or thoughts of self-harm, reach out for professional support immediately. Therapists can provide a safe space to explore your emotions, develop coping strategies, and navigate life’s transitions with guidance and care (Novaković et al., 2025).

At Summit Family Therapy, we honor the courage it takes to face life’s transitions. You do not have to navigate these changes alone. Together, we can explore your feelings, clarify your goals, and help you move forward with hope and confidence.

Sources

O'Donnell, M. L., et al. (2019). Adjustment Disorder: Current Developments and Future Directions. International Review of Psychiatry.

Novaković, I. Z., et al. (2025). Mental health during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences.

Peng, M., et al. (2025). Relationships between emotional intelligence, mental resilience, and adjustment disorder in newly licensed registered nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing.

Sundqvist, A. J. E., et al. (2024). The influence of educational transitions on loneliness and mental health among emerging adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence.

Parola, A., et al. (2025). Resources and personal adjustment for career transitions in adolescents. Journal of Vocational Behavior.

Integrating Nutrition and Lifestyle for Mental Health: A 2025 Update

Mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and ADHD are prevalent, affecting millions globally. Recent research underscores the significant role of nutrition and lifestyle interventions in managing these conditions, offering complementary approaches to traditional pharmaceutical treatments.

Mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and ADHD are prevalent, affecting millions globally. Recent research underscores the significant role of nutrition and lifestyle interventions in managing these conditions, offering complementary approaches to traditional pharmaceutical treatments.

🌱 Nutritional Psychiatry: A Growing Field

Nutritional psychiatry examines how dietary patterns and nutrients influence mental health. Studies indicate that dietary interventions can alleviate symptoms of depression and anxiety. For instance, a meta-analysis revealed that dietary interventions significantly reduced depressive symptoms compared to control conditions.

Furthermore, a comprehensive review highlighted the potential of specific nutrients, such as omega-3 fatty acids and B vitamins, in managing mood disorders.

🥗 The Mediterranean Diet: A Protective Pattern

The Mediterranean diet, rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, healthy fats, and lean proteins, has been associated with improved mental health outcomes. Adherence to this diet correlates with lower levels of depression and anxiety.

Conversely, high consumption of ultra-processed foods has been linked to increased risk of mental health issues, emphasizing the importance of dietary choices in mental well-being.

🍬 Sugar and Addiction: Implications for Mental Health

Excessive sugar intake can impact brain chemistry, potentially leading to addictive behaviors. Research suggests that sugar consumption activates dopamine and opioid pathways in the brain, similar to addictive substances.

Additionally, low dopamine levels associated with sugar withdrawal may contribute to cravings and continued consumption, highlighting the need for mindful dietary habits.

💤 Sleep: A Cornerstone of Mental Health

Quality sleep is crucial for mental health. Studies indicate that sleep disturbances are bidirectionally related to mood disorders, with poor sleep contributing to and resulting from conditions like depression and anxiety.

Implementing good sleep hygiene practices—such as maintaining a consistent sleep schedule, creating a restful environment, and limiting screen time before bed—can improve sleep quality and, by extension, mental health.

🏃♀️ Exercise: Enhancing Mood and Cognitive Function

Regular physical activity has been shown to elevate serotonin levels and regulate stress hormones, contributing to improved mood and cognitive function. Engaging in enjoyable activities, setting achievable goals, and exercising with a partner can enhance adherence and overall mental health benefits.

🧠 Integrating Approaches for Optimal Mental Health

Combining nutritional interventions with lifestyle modifications can accelerate therapeutic outcomes. For example, a ketogenic diet has shown promise in helping stabilizing mood and cognitive function in individuals with bipolar disorder.

Collaborating with healthcare providers trained in nutritional and integrative interventions can help individuals identify essential nutrients, develop personalized dietary strategies, and incorporate lifestyle changes to support mental health.

If you are interested in taking the next step in your mental and physical health, I have training in nutritional and integrative interventions. Give our office a call at 309-713-1485 or email info@summitfamily.net. I look forward to finding solution together!

Sources:

Opie RS, O’Neil A, Itsiopoulos C, et al. The impact of whole-of-diet interventions on depression and anxiety: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(11):2074-2093. PMC6455094

Jacka FN, O’Neil A, Opie R, et al. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the “SMILES” trial). BMC Med. 2017;15:23.

Harvard Health Publishing. Mediterranean diet may help ease depression. 2023.

Hall KD, et al. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: an inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. 2019;30(1):67-77.

Lenoir M, et al. Intense sweetness surpasses cocaine reward. PLoS One. 2007;2(7):e698.

Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:119-138.

Stanford Medicine. Sleep and mental health: What the science says. 2025.

Verywell Mind. What is sleep hygiene? 2024.

News-Medical.net. UCLA Health launches study on ketogenic diet for bipolar disorder in youth. 2025.

The Guardian. Metabolism and diet linked to bipolar depression, scientists say. 2024.

Nutritional and Integrative Interventions

How often do we read these mental health statistics and think that the only “cures” are pharmaceutical interventions?

Anxiety disorders are most common mental illness in US affecting 40 million adults (ADAA)

Depression affects 322 million adults worldwide

1 of every 6 adults will suffer depression in their lifetime

Nutritional and Integrative Interventions

(Depression, Anxiety, Bipolar and ADHD)

How often do we read these mental health statistics and think that the only “cures” are pharmaceutical interventions?

Anxiety disorders are most common mental illness in US affecting 40 million adults (ADAA)

Depression affects 322 million adults worldwide

1 of every 6 adults will suffer depression in their lifetime

Nutritional psychology is an emerging field that outlines how nutrients can affect mood and behavior. Many clients will see a reduction in symptoms when integrating non-pharmaceutical interventions to treat depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder and even ADHD.

It is possible to accelerate your therapeutic results by viewing the whole person:

Food: the good, the bad and the fake

Stress: A holistic approach

Exercise: Elevate serotonin and regulate stress hormones

Sleep: The 4 habits critical to sleep

Research shows that Mediterranean lifestyle--diet, physical activity, and socializing helps improve mental health/depression.

Sugar addiction--sugar as a substance releases opioids and dopamine which suggest an addictive potential

Fake nutrition--alcohol, junk food, snacks, sugar, soft drinks, white foods

Stress management--meditation, exercise, deep breathing, mindfulness, music, “ditch the screens”

Exercise--pick activity you enjoy, find a buddy, set a goal, start out slow

4 Sleep habits--adults need 7-9 hours of sleep in a dark, cool room. No caffeine after noon. Avoid electronic devices one hour before bedtime. Create a bedtime ritual.

“Let food be your medicine and medicine be your food.”---Hippocrates

S.A.D.--Standard American Diet is not recommended

High--Meat at center of plate, processed foods and simple carbohydrates

Low--healthy fats, fruits and vegetables

Healthy fats are important for brain health--avocado, coconut oil, EVOO, ghee

Proteins are important for brain health--fish, grass fed beef, eggs, nuts, seeds legumes

You can greatly increase your therapeutic results by addressing core physical and nutritional needs with a qualified counselor. You will discover the nutrients most essential to healthy brain function, treating depression and anxiety, and learn simple strategies that can be integrated with pharmaceutical interventions.

We have just scratched the surface here. There is so much more research and information about nutrition and mental health available. Professional counselors want to help you decipher and incorporate these practices into your life.

If you are interested in taking the next step in your mental and physical health, I have training in nutritional and integrative interventions. Give our office a call at 309-713-1485 or email info@summitfamily.net. I look forward to finding solution together!

Ambiguous Loss: What Is It?

Dr. Pauline Boss, PhD, from University of Minnesota, has spent most of her career studying and writing books about ambiguous loss. Have you considered how your life be impacted by an ambiguous loss? The following article is a brief summary of her findings.

Ambiguous Loss: What Is It?

Dr. Pauline Boss, PhD, from University of Minnesota, has spent most of her career studying and writing books about ambiguous loss. Have you considered how your life be impacted by an ambiguous loss? The following article is a brief summary of her findings:

What is an Ambiguous Loss?

Loss that remains unclear

Ongoing and without clear ending

Can’t be clarified, cured, or fixed

Ambiguous loss can be physical or psychological, but there is incongruence between absence/presence

Contextual: The pathology lies in a context or environment of ambiguity (pandemic, racism)

Two Types of Ambiguous Loss

Physical Absence with Psychological Presence--Leaving without saying goodbye

Catastrophic: disappeared, kidnapped, MIA

More common: leaving home, divorce, adoption, deployment, immigration

Psychological Absence with Physical Presence--Goodbye without leaving

Catastrophic: Alzeimer’s disease and of dementias, brain injury, autism, addiction

More Common: homesickness, affairs, work, phone obsessions/gaming, preoccupation with absent loved one

What Ambiguous Loss is NOT:

Death

Grief disorder

PTSD

Complicated grief

Ambivalence (different that ambiguous)

Examples of Ambiguous Loss Caused by Pandemic--loss of who we have been, what we have been doing, having control over lives, loss of our world view as safe place.

Our usual agency

Control over our usual personal, family, and work life

Our in person relationships

Our job; loss of money and financial security

Our sense of safety

The ability to control how much time we spend with family and friends

Ability to gather physically together in large numbers for worship, sports, concerts

Are you struggling with ambiguous loss? Our team of professionals at Summit Family Therapy can help. Give our office a call at 309-713-1485 or email info@summitfamily.net. You do not have to go through this alone.

Life Transitions: 8 Tips for Getting Through Tough Times

Life transitions are usually life changing events that cause us to re-examine our present sense of who we are. Although life transitions can happen at any age, many people will experience significant life transitions during mid-life or at retirement.

What is a Life Transition?

Life transitions are usually life changing events that cause us to re-examine our present sense of who we are. Although life transitions can happen at any age, many people will experience significant life transitions during mid-life or at retirement.

Examples of Life Transitions

Getting married

Pregnancy / Becoming a parent

Divorce or relational separation

Leaving parent’s home or moving to new home

Empty nest syndrome

Change in career or loss of career

Health changes / serious illness

Significant loss (person, pet, or anything important)

Retirement

If Life Transitions are normal, why do I feel so overwhelmed?

Transition means change. We are resistant to change. Most of us like predictability in our everyday lives. The unknown causes us fear and stress. We feel vulnerable. There can be a sense of grief or loss.

Are there any positives?

Changes, especially difficult changes, can promote personal growth. Dealing with a change successfully can leave a person stronger, more confident and better prepared for what comes next in life. Even unwanted or unexpected changes may produce beneficial outcomes.

You might gain new knowledge or develop new skills as the result of life transition. These changes might allow you to discover what’s important in your life and assist you in achieving greater self-awareness.

Coping with Change

Someone facing change may also experience depression, anxiety, changes in eating habits, trouble sleeping, or abuse of alcohol or drugs. If these symptoms persist or change disrupts normal coping mechanisms and makes it difficult or impossible for person to cope with new circumstances, a person may be diagnosed with an Adjustment Disorder. Symptoms typically begin within 3 months of the stress or change. It’s important to seek immediate assistance if you are engaging in reckless / dangerous behaviors or having thoughts of suicide—call 911.

Therapy for Change

A therapist may incorporate a variety of techniques such as emotionally focused therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, acceptance commitment therapy or motivational interviewing. A therapist will assist in treating stress, anxiety and depression while exploring new coping strategies with the client.

How can I cope with Life Transitions?

Understand that while Life Transitions are difficult, they can promote positive outcomes

Accept that change is a normal part of life

Identify your values and life goals

Learn to identify and express your feelings

Expect to feel uncomfortable

Take care of yourself

Build a support system

Don’t hurry- focus on rewards

Acknowledge what’s been left behind

If you are struggling with a Life Transition or significant change in your life, you may benefit by engaging in therapy with a professional counselor. Together you can identify your feelings, process the potential changes and formulate goals in order to move forward in your life.

Robin Hayles Joins Summit Full Time!

We have BIG news! Robin Hayles, MS, LCPC, CADC, has been working with us part time and is making the jump to full time private practice this March! She has immediate openings for new clients.

We have BIG news! Robin Hayles, MS, LCPC, CADC, has been working with us part time and is making the jump to full time private practice this March! She has immediate openings for new clients.

We are very excited to have her experience and client care make our team that much stronger. Robin offers Nutritional and Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions, Faith Based Counseling, Individual Counseling, and Couple Counseling. She currently serves Teens/Adolescents (14-18), Adults (19-64), and Seniors (65+).

Her counseling specialty areas are:

Depression

Anxiety

Grief, Loss, Life Transitions & Stress

Relationships

Trauma, Self Esteem & Self Image

Women’s Issues

Anger Management

Substance Abuse

Please join us in celebrating this milestone with Robin!